1. Why the Scale Is Misleading

Understanding exactly why body weight is an unreliable fitness progress indicator requires examining the specific variables that drive scale fluctuations independently of actual fat and muscle changes.

1-1. The Many Contributors to Body Weight

Total body weight is the sum of fat mass, lean mass (muscle, bone, organs, connective tissue), water (approximately 60 percent of total body weight), the contents of the digestive tract at any given time, and glycogen stored in muscle and liver tissue. Of these components, only fat mass and lean mass are the variables that fitness training is intended to affect — yet the other components (water, digestive contents, glycogen) fluctuate by 1 to 3 kilograms across a single day based on hydration status, sodium intake, food volume, hormonal cycles, and exercise type in ways that completely obscure the day-to-day signal of genuine fat and muscle change. The person weighing themselves after a high-carbohydrate dinner with extra sodium, before evacuating their bowels the next morning, may register 2 to 3 kilograms heavier than they did on an empty stomach the previous morning — despite having undergone zero change in fat or muscle mass in the intervening period. This variability makes single daily weigh-ins functionally useless as individual data points for evaluating body composition progress.

Hormonal cycles add another layer of variability that is particularly significant for women. Estrogen and progesterone fluctuations across the menstrual cycle produce systematic water retention patterns — typically 1 to 3 kilograms of additional water retention in the luteal phase (approximately 2 weeks before menstruation) that resolves with menstruation onset. A woman tracking weight on a daily basis without accounting for this cycle will observe what appears to be 1 to 3 kilograms of weight gain across the luteal phase — weight that disappears at menstruation onset and is replaced by apparent weight loss — producing a sawtooth pattern that repeats monthly and has nothing to do with fat mass changes. Interpreting this pattern without understanding its hormonal cause produces both false alarms (the luteal weight gain interpreted as fat gain requiring intervention) and false reassurance (the post-menstrual weight loss interpreted as fat loss validating the current approach).

1-2. The Body Recomposition Problem

Body recomposition — simultaneously reducing fat mass and increasing muscle mass — is one of the most commonly desired outcomes of fitness training and one of the most systematically misrepresented by body weight tracking. During successful body recomposition, fat and muscle masses change in opposite directions simultaneously — fat decreases while muscle increases — potentially leaving total body weight unchanged even as dramatic improvements in body composition occur. The person who has lost 3 kilograms of fat and gained 3 kilograms of muscle over 12 weeks of consistent training has achieved a genuinely significant body composition transformation: they are leaner, stronger, and more metabolically healthy than before. But their scale weight is unchanged — and if the scale is their only progress metric, they may conclude that their 12 weeks of training have produced nothing, abandon the program, and miss the substantial transformation that every other measurement method would clearly reveal.

1-3. Muscle Building Under Caloric Restriction

A related measurement problem occurs during fat loss phases that involve simultaneous muscle preservation or building. Research consistently shows that resistance training during caloric restriction preserves and in many cases increases lean mass while fat mass decreases — a highly desirable outcome that the scale systematically underestimates. The caloric restriction produces fat loss (which decreases scale weight) while the resistance training produces muscle gain (which increases scale weight) — and the net effect may be minimal scale change despite genuine and significant body composition improvement. Trainees tracking only body weight during a fat loss phase who are losing fat but gaining muscle may believe their caloric deficit is insufficient and reduce calories further — potentially below the threshold that supports muscle retention — based on misleading scale data that more comprehensive measurement methods would interpret correctly as successful recomposition.

1-4. Glycogen and Water: The Exercise-Induced Fluctuation

Exercise itself produces short-term scale weight changes that are unrelated to fat loss and are systematically misinterpreted when the scale is the primary progress metric. High-intensity and high-volume training depletes muscle glycogen stores — each gram of glycogen is stored with approximately 3 to 4 grams of water — producing rapid weight loss in the 24 to 48 hours following intense exercise that reflects glycogen depletion and water loss, not fat loss. Conversely, beginning a new resistance training program or returning after a break typically causes a temporary scale weight increase as muscles undergo the inflammation and water retention associated with the initial adaptation to unfamiliar training stress — a phenomenon sometimes called “newbie gains water weight” that routinely discourages new trainees who observe a scale weight increase in the first 1 to 2 weeks of their new program and incorrectly interpret this as fat gain.

1-5. When the Scale Is Useful

Despite its limitations, body weight has legitimate utility as one component of a comprehensive progress measurement system — specifically for tracking trends over time rather than interpreting individual daily measurements. A 4-week rolling average of daily morning weights filters the daily noise to reveal the genuine fat and muscle change trend beneath it, providing useful directional information (is total weight trending up, down, or flat over the past month?) that contextualizes the other measurement data. The scale is also useful for tracking extreme weight changes that would not be visible in other metrics — the significant unintentional weight loss that may signal a health issue, or the substantial weight gain over a bulking phase that would indicate excessive fat accumulation alongside the desired muscle gain. Used as one data point within a comprehensive measurement portfolio rather than as the primary progress metric, body weight contributes meaningful information. Used in isolation as the primary fitness progress measure, it produces more confusion and demotivation than genuine insight. The consistent finding across exercise adherence research is that people who track multiple progress dimensions — rather than relying on weight alone — are significantly less likely to abandon their programs during the inevitable periods of slow or stagnant scale progress that every fitness journey contains, because the multi-metric view reveals the genuine physiological progress that the scale is temporarily obscuring.

| Scale Reading | What It Could Mean | What You Actually Need to Know |

|---|---|---|

| Weight unchanged | Recomposition (fat lost + muscle gained) | Body composition — scale can’t tell |

| Weight increased 1–2 kg | Water retention, glycogen, food mass | Fat mass change only |

| Weight dropped 2 kg in a week | Mostly water/glycogen, not fat | True fat loss is ~0.5–1 kg/week max |

| Weight fluctuates +/-2 kg daily | Normal daily variation | Weekly average trend (4+ weeks) |

1-6. Reframing the Fitness Progress Narrative

The pervasiveness of scale-centric fitness progress thinking reflects a broader cultural narrative about fitness that equates physical transformation with body weight loss — a narrative that fitness marketing, before-and-after imagery, and popular weight loss programming have reinforced for decades. This narrative serves commercial interests by creating a simple, measurable, immediately compelling goal (lose weight) that generates ongoing product and service sales when the simple goal repeatedly fails to produce the lasting transformation it promises. The research on long-term weight loss outcomes is sobering: the majority of people who lose significant weight through caloric restriction without accompanying fitness development regain most or all of that weight within 3 to 5 years — not because of personal failure but because the loss of muscle mass that typically accompanies aggressive caloric restriction without training progressively lowers resting metabolic rate, making weight regain physiologically increasingly likely over time. The fitness narrative that produces better long-term outcomes — supported by decades of research on successful long-term body composition maintenance — is performance and health-focused rather than weight-focused: building and maintaining lean mass through consistent resistance training, developing cardiovascular fitness, and improving the specific biomarkers (blood pressure, blood glucose, lipid profiles, waist circumference) that predict long-term health rather than chasing a specific number on a scale that may or may not reflect genuine health improvement.

Adopting the multi-metric progress tracking framework described in this guide is not just a measurement strategy change — it is a narrative change. It shifts the fitness story from “I am trying to lose weight” (a goal that the scale arbitrates and that body weight fluctuation regularly frustrates) to “I am building strength, improving cardiovascular fitness, reducing body fat, and improving my energy and sleep” (a goal that multiple metrics collectively assess and that daily scale fluctuation cannot meaningfully disrupt). People who make this narrative shift consistently report better long-term exercise adherence, more positive relationship with their bodies, and ultimately better fitness outcomes than those who maintain the scale-as-arbiter framework — because the multi-metric narrative is more resilient to the inevitable measurement disappointments that single-metric tracking produces and more accurately reflects the genuine, multidimensional value of consistent physical fitness development.

The practical first step in making this narrative shift concrete and actionable is explicitly identifying, before beginning a tracking system, the specific fitness goals that matter most in terms of quality of life, functional capability, and daily wellbeing rather than appearance or scale weight: the ability to play with grandchildren without fatigue, the energy to be fully present and engaged through a long work day, the strength to carry heavy shopping without discomfort, the cardiovascular fitness to climb stairs easily, the flexibility to sit on the floor and stand without difficulty. These functional goals are more directly meaningful than aesthetic goals for most people’s actual lived experience, and tracking progress toward them — through the functional fitness metrics, energy ratings, and capability-based progress indicators described in this guide — produces a more authentic and more durable motivational foundation than scale weight optimization ever can.

2. Body Composition Measurement Methods

Body composition measurement — the assessment of fat mass versus lean mass as proportions of total body weight — provides the information that body weight alone cannot: whether weight changes reflect changes in fat, muscle, or both, and whether total body composition is moving in the intended direction.

2-1. DEXA Scan: The Gold Standard

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scanning is widely considered the most accurate body composition measurement method available outside research laboratory settings, providing simultaneous measurement of fat mass, lean mass, and bone mineral density with a margin of error of approximately 1 to 3 percent. DEXA scans also provide regional body composition data — separating the composition of trunk, arms, legs, and android (belly) versus gynoid (hip/thigh) fat distribution — that provides clinically relevant information about health risk distribution beyond the total body composition picture that other methods provide. The primary limitations of DEXA are cost ($50 to $150 per scan depending on location) and access (requiring a clinical facility with DEXA equipment), making it impractical as a frequent monitoring tool for most recreational fitness enthusiasts. For periodic benchmark measurements every 3 to 6 months, however, DEXA provides the most accurate body composition data available outside research settings and is a worthwhile investment for anyone with specific body composition goals who wants the most reliable measurement of whether their program is producing the intended changes.

2-2. Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis (BIA)

Bioelectrical impedance analysis — the technology used in most consumer body composition scales and handheld body fat analyzers — estimates body fat percentage by measuring the resistance of an electrical current passed through the body, using the differential conductivity of fat tissue (poor conductor) and lean tissue (good conductor) to calculate their proportions. Consumer BIA devices are inexpensive ($30 to $200), convenient (home use, instant results), and can be used as frequently as desired — making them the most practically accessible body composition measurement tool for most people. The primary limitation of BIA is measurement variability: hydration status, food intake, exercise timing, skin temperature, and the specific device’s algorithm all affect BIA readings by 3 to 5 percentage points in ways that are unrelated to actual body composition. This variability means that individual BIA measurements are too unreliable to interpret accurately, but trends across multiple measurements taken under highly standardized conditions (same time of day, same hydration status, same time relative to eating and exercise, same device) can reveal genuine body composition trends with reasonable reliability.

For home use, the most reliable BIA measurement protocol: weigh and measure body fat first thing in the morning, after using the bathroom but before eating or drinking, having avoided alcohol for 24 hours and intense exercise for 12 hours, and having slept for at least 7 hours. Taking measurements under this standardized protocol weekly and calculating a 4-week rolling average reduces the measurement noise to a level where genuine body composition trends become visible. Individual readings under this protocol will still vary by 1 to 2 percentage points from session to session, but the rolling average will reflect genuine body composition trends rather than measurement noise — providing useful directional information about whether body fat percentage is trending in the intended direction over 4 to 8-week periods.

2-3. Skinfold Calipers

Skinfold caliper measurement — using calibrated calipers to measure the thickness of subcutaneous fat at standardized body sites — provides body fat percentage estimates with accuracy comparable to BIA when performed correctly and consistently by the same practitioner. The major advantage of skinfold measurement over BIA is that caliper readings are not affected by hydration status — the primary source of BIA variability — making them more reliable as individual measurements rather than only as aggregated trend data. The limitations are the skill and consistency of the practitioner (self-measurement with calipers is possible but more variable than practitioner measurement), the number of sites measured (3-site protocols are faster but less accurate than 7-site protocols), and the quality of the caliper ($10 plastic calipers are significantly less accurate than $50 to $200 calibrated metal instruments).

2-4. Circumference Measurements

Tape measure circumference measurements at standardized body sites — waist, hips, chest, arms, thighs, calves — provide body composition trend data that is free, requires only a flexible tape measure, and is not affected by hydration, food intake, or any of the other variables that affect scale weight and BIA readings. The waist circumference in particular is one of the most clinically meaningful individual body composition metrics available: research consistently shows that waist circumference is strongly correlated with visceral fat accumulation (the metabolically active fat tissue surrounding internal organs that is most strongly associated with cardiometabolic disease risk), and that reductions in waist circumference are among the most reliably motivating progress signals for people in fat loss phases. A waist circumference measurement taken weekly under consistent conditions (same time of day, same level of the navel, with the tape level and without compression) provides a reliable, motivating progress signal that the scale cannot replicate — and that is particularly valuable for women in the luteal phase whose scale weight is temporarily elevated by water retention but whose tape measure correctly reflects the ongoing fat loss that continues regardless of the hormonal water retention pattern.

2-5. The Circumference Ratio Approach

Beyond absolute circumference measurements, the waist-to-hip ratio and waist-to-height ratio provide body composition health metrics with strong research support for their predictive value for metabolic and cardiovascular health risk. A waist-to-hip ratio below 0.85 in women and 0.90 in men is associated with substantially lower cardiometabolic disease risk than ratios above these thresholds. A waist-to-height ratio below 0.5 is associated with significantly lower disease risk regardless of sex — the “keep your waist circumference below half your height” guideline is one of the simplest and most evidence-supported body composition health targets available. Tracking these ratios over time as fitness improves — and noting the threshold crossings that indicate genuine improvements in health risk profile — provides motivating, clinically meaningful progress markers that connect fitness improvement to long-term health outcomes in concrete, measurable terms.

| Method | Accuracy | Cost | Frequency Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| DEXA scan | High (±1–3%) | $50–$150/scan | Every 3–6 months |

| BIA scale (standardized) | Moderate (±3–5%) | $30–$200 (one-time) | Weekly average |

| Skinfold calipers | Moderate-high | $10–$200 | Monthly (same practitioner) |

| Tape measure circumference | Indirect but reliable trend | $5–$10 | Weekly |

2-6. Building a Body Composition Measurement Calendar

The practical implementation of a multi-method body composition measurement system requires a structured calendar that specifies when each measurement method is used, under what conditions, and how the results are integrated into the overall progress picture. A practical body composition measurement calendar for a goal-focused recreational exerciser: daily morning weight (used only as raw data for rolling average calculation, not interpreted individually); weekly standardized BIA reading (same morning protocol, contributes to monthly body fat trend); monthly tape measure circumference at waist, hips, right thigh, and right upper arm (quantitative tracking of regional composition changes); monthly progress photos under standardized protocol (visual body composition assessment); and every 3 to 6 months, a DEXA scan for precise body composition benchmarking. This calendar distributes measurement effort appropriately across methods, prevents over-reliance on any single method, and ensures that sufficient data is collected at each time resolution to detect genuine trends above measurement noise.

The monthly integration review is the analytical step that makes the measurement calendar useful rather than merely data-accumulative. At the end of each month, the complete body composition picture is assembled from all available data: the 4-week rolling average weight trend (direction and rate of change), the monthly BIA reading compared to the previous month (body fat percentage trend), the tape measure changes at each site (where is fat being lost or muscle being gained?), the progress photo comparison (visual assessment of changes), and if available, the DEXA data from the periodic benchmark scan. Together, these five data streams provide a comprehensive, multi-dimensional body composition assessment that identifies whether the current training and nutrition approach is producing the intended changes, where the most significant changes are occurring, and whether any measurement-specific anomalies (an elevated BIA reading due to illness, for example) should be discounted rather than interpreted as genuine body composition change. This integration review is the payoff of the consistent measurement practice — the analytical synthesis that converts raw data into genuinely actionable insights that single-metric tracking could never provide.

These population-specific adaptations to the measurement calendar recognize that standardized protocols designed for average healthy adults do not automatically provide accurate and comparable data across the full diversity of individual circumstances — and that measurement protocols that account for known sources of population-specific variability provide meaningfully more accurate trend data than uncritical application of a universal protocol regardless of the individual’s specific physiology and life circumstances. Special populations require specific adaptations to the body composition measurement calendar that account for the measurement limitations most relevant to their circumstances. Women tracking body composition should synchronize their monthly measurement timing to the same phase of the menstrual cycle each month — typically the 3 to 5 days following menstruation when water retention is at its monthly minimum and measurements are most comparable across months. Older adults should include muscle mass tracking (lean mass via DEXA, or anthropometric proxies such as mid-upper arm circumference) as a specific measurement priority given the clinical importance of sarcopenia prevention in healthy aging. Athletes in periodized training should time measurement periods to occur during deload or rest weeks rather than immediately following high-volume training blocks, when glycogen and water retention from training load would artificially inflate weight and BIA readings relative to the true body composition baseline.

The monthly integration review closes the measurement loop that transforms raw data into actionable understanding.

3. Strength and Performance Tracking

Strength and performance metrics are among the most accurate, most motivating, and most directly relevant measures of fitness progress available — and they are entirely independent of the scale weight fluctuations that make body weight such an unreliable progress indicator.

3-1. Why Performance Metrics Matter More Than You Think

Performance improvements are direct, objective evidence of physiological adaptation — there is no measurement noise, no hydration variability, no confounding factor that can explain why you can now lift more, run faster, or perform more reps than you could six weeks ago. When your barbell squat increases from 80 to 100 kilograms over 12 weeks of consistent training, the improvement is unambiguous: your neuromuscular system has become more efficient, your relevant muscle mass has developed, and your connective tissue has adapted to support greater loading — regardless of what the scale shows on any given day. Performance tracking provides the most direct evidence available that training is working — evidence that the scale cannot contradict or obscure, because performance improvement and body composition improvement are not inversely related in the way that the scale-as-primary-metric framing implies.

The motivational power of performance tracking is particularly important during body recomposition phases, fat loss phases with simultaneous muscle building, and the early weeks of any new training program when scale weight is often temporarily elevated by training-induced water retention. Watching strength increase, endurance improve, and skills develop during these periods provides genuine evidence of program effectiveness that sustains motivation through the scale confusion that these physiologically complex adaptation phases produce. In my own experience, switching from scale-primary to performance-primary progress tracking during a body recomposition phase was the single change that transformed my subjective experience of the phase from discouraging (the scale appeared stagnant) to motivating (every week produced new performance records) — with no change to the training program or the actual physiological adaptations occurring.

3-2. Strength Testing Protocols

Formal strength testing provides objective benchmark data for the major strength movements that tracks neuromuscular and muscular development across the training period. The most commonly tested strength benchmarks for recreational trainees: one-repetition maximum (1RM) in the squat, deadlift, bench press, and overhead press for gym-based trainees; maximum pull-ups or push-ups in a single set for bodyweight trainees; timed holds for static exercises (plank, wall sit, L-sit). Testing protocols should be standardized: same time of day (when fully rested), same warm-up sequence before each test, same rest periods between testing sets, and testing performed no more frequently than every 4 to 6 weeks to allow sufficient recovery between testing sessions and to detect genuine strength development trends above session-to-session performance variability. Logging the test results in a dedicated testing record alongside the date and the training conditions (sleep quality, nutrition timing, stress level) provides context for interpreting performance variation and distinguishing genuine strength changes from temporary performance fluctuations driven by non-training variables.

3-3. Training Volume as a Progress Indicator

Total training volume — the product of load × sets × reps across a workout or training period — is a continuous progress metric that can be tracked at every session without the formal testing protocol that maximum strength testing requires. Progressive volume increases within a training program reflect the combination of increasing strength (heavier loads) and increasing work capacity (more sets and reps at a given load) that constitute genuine fitness development. Volume tracking is particularly valuable for identifying the early signs of overtraining (volume that was previously manageable becoming increasingly difficult to complete), the effectiveness of deload periods (volume restoration and performance recovery following planned recovery weeks), and the long-term trajectory of training development across months and years of consistent practice. A simple training log that records all sets, reps, and loads for each session provides the data for retrospective volume calculation and trend analysis that tells the full story of long-term fitness development in a way that isolated performance tests cannot capture.

3-4. Cardiovascular Performance Benchmarks

Cardiovascular fitness progress is reliably tracked through standardized performance benchmarks that measure the cardiovascular and endurance adaptations that training produces. Key benchmarks: timed completion of a fixed distance (run 5K as fast as possible, record time; row 2,000 meters, record time; cycle 10 kilometers, record time); distance covered in a fixed time (how far can you run in 12 minutes — the Cooper test, validated in decades of cardiovascular fitness research); heart rate at a fixed workload (exercise at a specific pace or power output and record heart rate — lower heart rate at the same workload indicates improved cardiovascular efficiency); and resting heart rate (a long-term marker of cardiovascular fitness development, typically declining by 5 to 15 beats per minute across months of consistent aerobic training in previously untrained individuals). Any of these benchmarks tracked monthly provides an accurate, motivating measure of cardiovascular fitness development that body weight cannot reflect.

3-5. Functional Fitness Tests

Functional fitness tests assess the practical physical capabilities that training is intended to develop — the ability to perform real-world physical tasks, maintain balance and coordination, and execute fundamental movement patterns with quality and ease. Common functional fitness benchmarks: the sit-and-reach test (hamstring and lower back flexibility); the single-leg balance test (proprioception and ankle stability — timed eyes-closed single-leg stand); the overhead squat assessment (simultaneous test of hip, ankle, and thoracic mobility); grip strength (measured via hand dynamometer or timed dead hang, strongly correlated with overall strength and longevity research); and vertical jump height (lower body explosive power and neuromuscular coordination). These functional tests provide progress metrics that are directly relevant to quality of life and injury prevention in ways that barbell strength metrics and cardiovascular benchmarks do not fully capture — and that often reveal fitness dimensions being neglected by the current training program when specific functional deficits emerge.

| Performance Metric | How to Test | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Strength (gym) | 1RM squat/deadlift/bench/press | Every 4–6 weeks |

| Strength (bodyweight) | Max pull-ups / push-ups in one set | Monthly |

| Cardiovascular | Timed 5K run or 12-min Cooper test | Monthly |

| Endurance | Training volume log (total sets × reps × load) | Every session |

| Functional | Sit-and-reach, balance test, vertical jump | Every 6–8 weeks |

3-6. Tracking Athletic Skill Development

For many fitness enthusiasts — particularly those pursuing calisthenics, martial arts, yoga, sport-specific training, or any movement-skill-based practice — the development of athletic skills represents a progress dimension that conventional fitness metrics (body weight, body fat percentage, one-repetition maximum) completely fail to capture. The calisthenics practitioner developing toward a handstand, a muscle-up, or a front lever is achieving genuine, measurable, highly demanding physical development — development that requires months of consistent practice, produces real strength and coordination adaptations, and creates motivating progress milestones that sustain engagement through the long development timeline these advanced skills require. Tracking skill development requires a different measurement approach than physical performance benchmarks: video recording of skill attempts at regular intervals (monthly or every two weeks for skills in active development), qualitative assessment of specific technical elements (degree of body alignment, control at sticking points, consistency of success across attempts), and milestone documentation (first successful attempt at a new skill or variation) provide the skill progress record that motivates continued practice and makes visible the incremental technical improvements that are otherwise invisible in the subjective experience of repeated practice.

Video recording is particularly valuable for skill development tracking because the practitioner rarely has an accurate perception of their own movement quality during execution — proprioceptive feedback during complex movements is often misleading, and the difference between a technically sound and technically flawed handstand is far more visible on video than it feels during the attempt. Monthly video review of skill attempts, compared against previous months’ recordings, provides both the objective technical feedback needed for skill correction and the motivating visual evidence of technical improvement that sustains the motivation for the patient, consistent practice that skill development requires. The contrast between a first attempt at a handstand push-up — typical result: collapsing immediately from the inverted position, unable to maintain spinal alignment or control the descent in any meaningful way — and a 6-month video showing controlled descent, full range of motion, consistent technique across multiple consecutive reps, and the confident physical presence that skill mastery produces, is one of the most dramatic, most personally meaningful, and most immediately motivating progress demonstrations available in all of fitness training, and one that no amount of body weight data, body fat percentage, or barbell maximum lift data could ever capture or meaningfully convey.

For practitioners whose primary fitness goal is functional movement quality rather than aesthetic appearance or performance metrics — the yoga practitioner pursuing deeper and more stable poses, the mobility-focused trainer working toward pain-free movement in daily life, the aging adult rebuilding fundamental movement patterns to maintain independence, or the person rebuilding movement quality after injury or extended inactivity — qualitative movement assessment by a qualified practitioner or via systematic video comparison against a clear reference standard provides the most direct and relevant progress measurement available for their specific training goals. Comparing current performance of a fundamental movement pattern (overhead squat, single-leg deadlift, deep squat hold) to a reference video of optimal technique, or to the practitioner’s own previous attempt from 4 to 8 weeks prior, provides a movement quality progress assessment that is directly relevant to the functional health, pain reduction, and injury prevention goals that movement-focused training serves. These movement quality improvements are among the most meaningful fitness developments a person can achieve for long-term physical health — and they are the ones that conventional physical metrics of body composition and maximal performance completely overlook despite their profound relevance to daily function and quality of life.

4. Progress Photos: The Visual Record

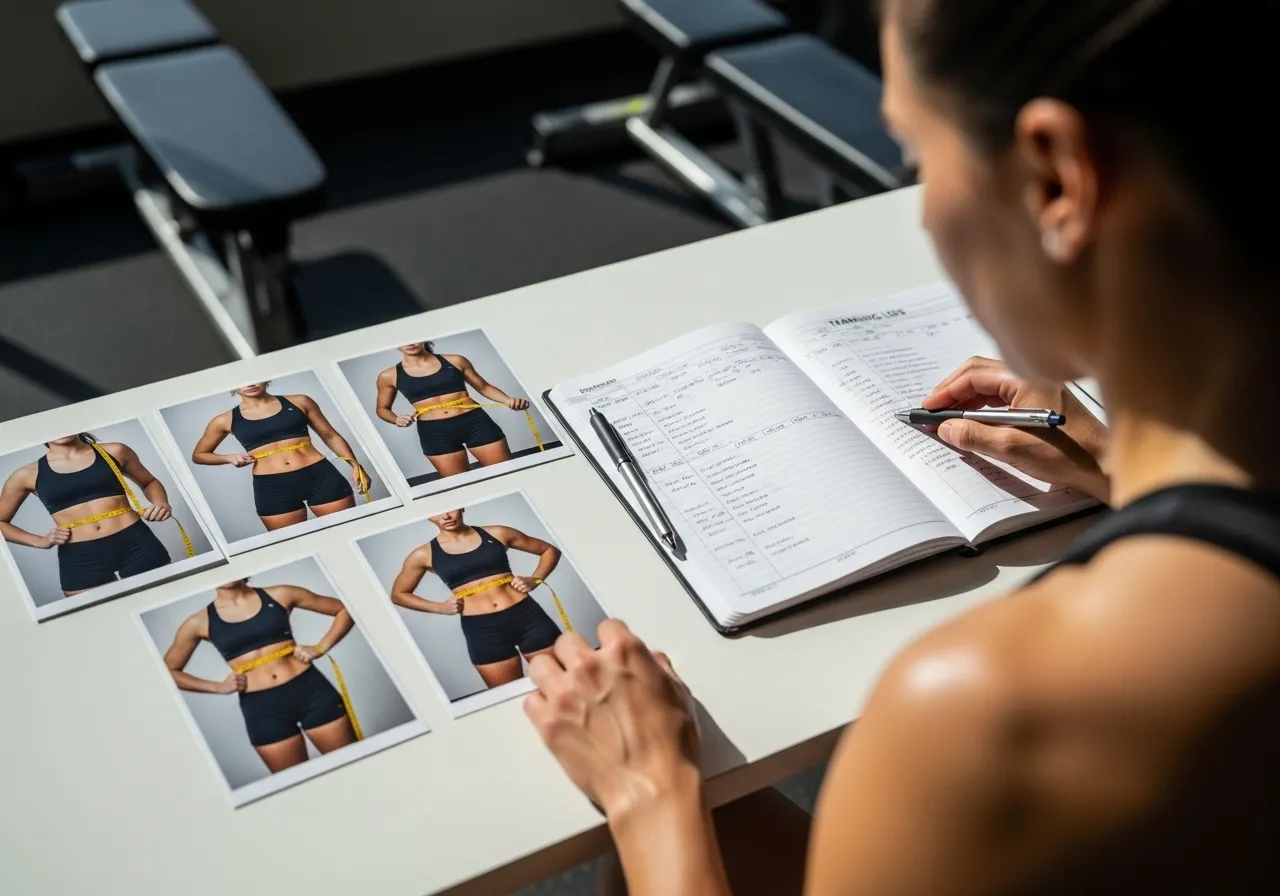

Progress photography — taken consistently, under standardized conditions, at regular intervals — provides the visual body composition data that scales and circumference measurements describe numerically but cannot depict concretely, and that is uniquely motivating for many people because it shows the physical transformation in the form that the human visual system most directly processes.

4-1. Why Progress Photos Work

The human brain is substantially better at detecting visual pattern changes than at interpreting numerical data changes — a finding that reflects the primacy of visual processing in human cognition and that has direct implications for fitness motivation. A 3 percent reduction in body fat percentage is a meaningful physiological change that represents approximately 2 kilograms of fat loss for a 70-kilogram person, but the number “3 percent” carries limited emotional resonance. The visible difference between two photos taken 8 weeks apart — a measurably smaller waist, more visible muscle definition, different posture and body proportions — communicates the same change in a form that activates the visual reward systems that numerical data does not, producing the genuine motivational response that sustains continued training effort. Research on visual feedback and fitness motivation consistently finds that progress photos are among the most motivating forms of progress evidence available — more motivating for most people than equivalent changes demonstrated through numbers alone.

Progress photos also capture the specific visual changes that matter most to the individual in a way that generalized metrics cannot. Two people with identical body fat percentage changes may undergo visually very different transformations depending on where their fat distribution shifts and where muscle develops — and a progress photo captures the specific transformation of the specific body in a way that population-average measurement methods cannot. The person whose fat loss is concentrated in the midsection will see dramatically different progress in a waist-up photo than the person whose fat loss is more uniformly distributed — and the progress photo faithfully depicts each individual’s specific transformation rather than forcing the individual result through a population-average measurement framework that may not accurately capture it.

4-2. The Standardized Photo Protocol

The consistency of photographic conditions is the single most important factor in the usefulness of progress photos — inconsistent conditions produce photos that are not comparable across time and that can create the false impression of regression or dramatic rapid progress based entirely on lighting, posing, or hydration differences rather than actual body composition change. The essential standardization elements: always photograph at the same time of day (morning, after using the bathroom but before eating, provides the most consistent and typically most favorable body composition representation); always use the same lighting (natural window light from the same direction, or a consistent artificial light source — avoid direct flash, which flattens muscle definition); always maintain the same distance from the camera and the same camera angle (eye-level or slightly below, full-body or torso-only depending on the goal); always wear the same clothing (or the same minimal clothing that shows the target areas without significant body covering); and always take the same poses — front, side (both sides if desired), and back — in the same relaxed posture rather than flexed or deliberately posed for favorable appearance.

4-3. Frequency and Comparison Strategy

Weekly progress photos provide sufficient data frequency for most goal timelines while minimizing the frustration of comparing photos that are too close together to show visible change. The optimal comparison strategy: do not compare today’s photo to last week’s photo — the changes are too subtle to be reliably visible at a one-week interval for most people at a healthy rate of body composition change. Compare instead at 4-week intervals (this week versus 4 weeks ago) for a comparison window that is long enough to show genuine visible change while short enough to provide near-term progress visibility. Additionally, maintain a photographic record that allows 3-month and 6-month comparisons — the longer time horizons that reveal the cumulative transformation most dramatically and that provide the most powerful motivational evidence when visible progress at shorter intervals has been disappointing.

4-4. Managing the Psychological Relationship with Progress Photos

Progress photography has genuine psychological risks that deserve acknowledgment and proactive management. For people with existing body image concerns, eating disorder history, or dysmorphic tendencies, regular progress photography can intensify body-focused cognition, increase dissatisfaction with current appearance, and reinforce the evaluative relationship with physical appearance that healthy fitness motivation seeks to move beyond. The healthy relationship with progress photography frames each photo as data — a measurement, like a tape measure reading or a performance test result — rather than as a judgment of physical attractiveness or personal worth. The progress photo is a record of change over time, not a current evaluation of how good or bad the body looks; its purpose is comparison across time, not assessment against an external aesthetic standard.

4-5. Digital Tools for Photo Comparison

Several smartphone apps and photo tools simplify the standardized progress photo process and the comparison across time points. Apps like Progress (specifically designed for fitness progress photography), Nudge Coach, and various general photo comparison apps allow side-by-side photo comparison with aligned body positioning, automated date labeling, and selective sharing features that maintain privacy while enabling social accountability. The standardization features of these apps — grid overlays for positioning consistency, size normalization for distance consistency, and date-stamped storage — address the most common sources of progress photo inconsistency and make the comparison process more reliable and less dependent on manual standardization effort. For people committed to using progress photography as a primary progress metric, a dedicated progress photo app that stores the complete photo history with date stamps and enables easy comparison across any two time points provides substantial practical value over informal phone camera photo management.

| Photo Element | Standardize To | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Timing | Morning, post-bathroom, pre-eating | Minimizes daily variation in appearance |

| Lighting | Consistent natural or artificial source | Muscle definition perception depends on lighting |

| Distance/angle | Same room position, eye-level camera | Size comparison requires consistent distance |

| Clothing | Same minimal clothing each time | Clothing hides and distorts body shape |

| Posture/pose | Same relaxed standing pose, front/side/back | Posture dramatically affects apparent physique |

4-6. Sharing Progress Photos Responsibly

The decision of whether and how to share progress photos publicly — on social media, in online fitness communities, or with training partners — involves considerations that go beyond the measurement utility of the photos themselves, touching on privacy, psychological wellbeing, and the social dynamics of online fitness culture. Sharing progress photos publicly creates accountability and community connection that can genuinely support exercise motivation; research on public commitment to fitness goals consistently finds that publicly shared goals generate stronger behavioral commitment than privately held ones. The fitness communities that form around shared progress journeys — the Reddit body transformation subreddits, the Instagram fitness accountability communities, the private transformation challenge groups — provide genuine social support, expert feedback, and shared motivation that benefit many participants and that progress photo sharing enables.

The risks of public progress photo sharing deserve equal attention. Online fitness communities can expose progress photos to comparison culture, unsolicited critical commentary, and social validation dynamics that shift the motivation for fitness from intrinsic (training because it feels good and supports health) to extrinsic (training for social approval that must be continuously re-earned through visible progress). Research on social media use and body image consistently finds that exposure to idealized fitness imagery — even on communities ostensibly focused on achievable transformation rather than elite aesthetics — increases body dissatisfaction, particularly in women and younger adults. The decision to share progress photos publicly should weigh the accountability and community benefits against the body image and social validation risks for each individual’s specific psychological profile — with extra caution for anyone with existing body image concerns, comparison sensitivity, or history of disordered eating.

Clearly articulating to yourself precisely what you hope to gain from sharing before actually doing so — accountability, community, technical feedback, or simply documentation — and then honestly and periodically reassessing whether the actual lived experience of sharing is consistently producing those intended benefits rather than the comparison anxiety, body image distress, or approval-seeking behavior that online sharing frequently generates in participants who did not anticipate these effects, is the critical self-monitoring practice that keeps public progress photo sharing in the motivationally beneficial rather than psychologically counterproductive zone for your specific psychology and circumstances. A middle path that captures most of the accountability benefits of public sharing without the exposure risks: share progress photos with a small, trusted, private group — a few training partners, a dedicated accountability buddy, or a small private group in a closed social media space — rather than publicly to an unrestricted online audience. This approach provides the social commitment and genuine personal connection that sustain motivation while limiting exposure to the anonymous comparison culture and unsolicited criticism that public sharing risks. Private sharing with people who genuinely know you, understand your specific goals, and are invested in your wellbeing as an individual rather than as an inspiring transformation story produces stronger accountability effects, more personally meaningful encouragement, and more useful honest feedback than public sharing with a large anonymous audience whose engagement is primarily performance-based. This makes the private accountability relationship both the psychologically safer and the motivationally more effective long-term progress sharing approach for most people who do not already possess a thoroughly resilient, comparison-immune body image that is not vulnerable to the powerful social comparison dynamics that public online fitness communities reliably and persistently generate in the majority of their participants.

In all cases, the goal of progress photo sharing is to serve the fitness journey — not to transform the fitness journey into a content production project whose demands compete with the training itself for time, energy, and attention. Keeping this priority clear prevents the sharing practice from becoming counterproductive to the very progress it was intended to document and celebrate.

5. Subjective and Lifestyle Progress Metrics

Fitness progress extends beyond the physical metrics of body composition and performance into the subjective dimensions of wellbeing, energy, sleep quality, mood, and daily function that represent the actual quality-of-life benefits that motivate most people to pursue fitness in the first place.

5-1. Energy Levels and Daily Vitality

One of the most reliably reported and most personally meaningful outcomes of consistent exercise is improvement in daily energy levels — the sustained, non-caffeinated energy and cognitive alertness across the day that regular exercisers describe as one of the primary reasons they continue training regardless of aesthetic or performance goals. The mechanism is well-established: regular aerobic and resistance exercise improves mitochondrial density and efficiency in muscle tissue, improves cardiovascular efficiency (the heart moves more blood per beat, requiring less effort at any given activity level), optimizes cortisol rhythms that regulate diurnal energy cycles, and improves sleep architecture — all producing the subjective experience of more stable, more sustained daily energy that the sedentary comparison condition does not provide. Tracking subjective energy levels on a simple 1 to 10 daily scale and calculating weekly averages provides a longitudinal energy progress metric that captures the quality-of-life improvement that training produces — improvement that body composition and performance metrics do not measure.

5-2. Sleep Quality as a Fitness Progress Marker

Sleep quality improvement is one of the most consistent fitness benefits reported in exercise research — and one of the most practically important for the overall health and fitness progress that adequate sleep enables. Research meta-analyses on exercise and sleep consistently find that regular physical activity reduces sleep onset latency (time to fall asleep), increases total sleep duration, improves slow-wave sleep depth and proportion, and reduces nighttime waking — improvements that translate directly into better daytime cognitive function, better emotional regulation, better recovery from training, and better hormonal environment for body composition improvement. Tracking subjective sleep quality (ease of falling asleep, sleep depth, morning alertness) and objective sleep data (total sleep time, waking frequency via wearable sleep tracker) provides a fitness progress metric that captures the sleep dimension of health improvement that body composition and performance metrics overlook entirely. Many people report that sleep quality improvement is the fitness benefit they notice first — often within the first 2 to 3 weeks of consistent exercise — and that it is one of the primary self-reinforcing rewards that sustains their exercise habit before more visible body composition or performance improvements become apparent.

5-3. Mood and Psychological Wellbeing

The antidepressant and anxiolytic effects of regular exercise are among the most robustly documented findings in mental health research — with multiple meta-analyses confirming that exercise produces improvements in depression and anxiety symptom severity comparable to pharmacological interventions in mild to moderate cases, and that the mood benefits of acute exercise persist for 2 to 4 hours post-exercise with chronic benefits accumulating across weeks and months of consistent practice. Tracking mood and psychological wellbeing as fitness progress metrics — through validated brief scales (the PHQ-2 for depression, the GAD-2 for anxiety, or simple daily mood ratings on a 1 to 10 scale) — provides evidence of the mental health improvements that training produces and that are invisible in body composition and performance data. For many people, the mood and energy benefits of exercise are more immediately motivating than physical appearance changes and more personally meaningful than performance metrics — making them the most important progress dimension to explicitly track and acknowledge for long-term exercise motivation maintenance.

5-4. Functional Daily Life Improvements

Fitness improvements manifest in daily life activities in ways that are directly meaningful for quality of life and that provide progress evidence in the moments when performance testing and photo comparisons are not occurring. The ability to climb stairs without becoming breathless that was impossible 3 months ago. The capacity to play actively with children or grandchildren without fatigue that previously ended the activity after minutes. The ease of carrying heavy shopping bags that previously required multiple trips or assistance. The reduced lower back discomfort after a day of desk work that previously was a daily experience. The ability to stand for extended periods that was previously limited by leg fatigue. These functional improvements are direct evidence of cardiovascular fitness, strength, and endurance development in the contexts that actually matter for daily life quality — and they are experienced continuously throughout each day, providing near-constant, contextually embedded reinforcement of the fitness improvements that formal testing only captures periodically.

5-5. Building a Comprehensive Progress Dashboard

The most complete and most motivating progress tracking system integrates multiple metrics from different measurement categories into a comprehensive dashboard that provides a holistic picture of fitness development across all its important dimensions. A practical progress dashboard for a recreational fitness enthusiast: weekly average body weight (trend, not individual readings); monthly body composition snapshot (BIA reading under standardized conditions, or tape measure circumference at waist, hips, and thigh); monthly performance benchmarks (strength test results or time trial results depending on primary goals); 4-week progress photo comparison; and weekly subjective metrics (energy, sleep quality, mood ratings). This five-component dashboard takes approximately 20 minutes per month to complete and provides incomparably more accurate and more motivating progress information than the single scale reading that most people use as their sole progress metric. When any single component shows disappointing results — the scale stagnant, the BIA temporarily elevated, the performance test below expectations — the other components are typically showing genuine positive progress that prevents the all-or-nothing discouragement that single-metric tracking produces.

| Subjective Metric | How to Track | What Progress Looks Like |

|---|---|---|

| Daily energy | 1–10 scale, weekly average | Weekly average trending upward over months |

| Sleep quality | Wearable + subjective rating | Faster sleep onset, less waking, better mornings |

| Mood | Daily 1–10 or validated scale monthly | Weekly averages improving; fewer low days |

| Functional capacity | Qualitative notes on daily activities | Stairs easier, kids play possible, bags lighter |

5-6. The Wellbeing Metrics That Predict Long-Term Fitness Success

Research on long-term exercise adherence identifies several subjective wellbeing metrics that are stronger predictors of whether someone will still be training consistently in 5 years than any physical performance or body composition metric measured at the beginning of a fitness program. Exercise enjoyment — the degree to which training sessions are experienced as genuinely pleasant rather than purely obligatory — is the most powerful long-term adherence predictor identified across multiple longitudinal studies, outperforming goal commitment, fitness knowledge, and even initial motivation level in predicting who maintains consistent exercise across multi-year follow-up periods. Exercise self-efficacy — the confidence in one’s ability to maintain the exercise program through difficulties and disruptions — is the second most powerful predictor, with higher self-efficacy at program initiation associated with substantially better 2 and 5-year adherence outcomes. Social integration — whether exercise provides meaningful social connection or is experienced in positive social contexts — is the third major predictor, reflecting the fundamental human need for social belonging that fitness communities, training partnerships, and group exercise formats address.

Deliberately and consistently tracking these three evidence-identified wellbeing metrics — exercise enjoyment rated on a simple 1 to 10 scale captured immediately after each training session while the experience is fresh, exercise self-efficacy assessed monthly through a brief honest rating of confidence in maintaining the current program through the next month’s challenges, and social exercise experience assessed through qualitative tracking of whether training is providing meaningful social connection or is experienced as isolating and disconnected — provides early warning indicators of long-term adherence risk that physical metrics cannot reveal. A person whose performance metrics are steadily improving and whose body composition measurements are moving in the intended direction but whose post-session enjoyment ratings have been consistently declining across 4 to 6 weeks of training is at meaningfully elevated risk of program abandonment within the following 3 to 6 months — not because the program is ineffective physiologically but because the declining enjoyment is eroding the intrinsic motivation that sustains long-term training in the absence of external pressure. Identifying this pattern through enjoyment tracking and intervening — adding training variety, incorporating social exercise, exploring different movement modalities — can preserve the adherence that the declining enjoyment was threatening before the program abandonment actually occurs.

The social connectedness dimension of fitness is particularly important to track explicitly for home trainers and those who exercise alone, because the social isolation of training without community connection is one of the most significant risk factors for long-term exercise dropout that these training contexts create. A home trainer who consistently rates their training as socially isolating, who has no fitness accountability relationships, and whose training provides no meaningful social engagement is at meaningfully higher dropout risk than an equivalent home trainer who participates in an online fitness community, has at least one training accountability relationship, and occasionally trains in social contexts. Identifying the social isolation risk through wellbeing tracking and addressing it proactively — building at least one specific accountability relationship with clear structure and regular communication, joining a relevant online fitness community that provides genuine engagement rather than passive content consumption, scheduling periodic in-person or synchronous social training experiences — protects long-term adherence in a way that no amount of optimized physical progress tracking, program design refinement, or motivational content consumption can substitute for. Social connection is a fundamental human need whose presence or absence in the training experience exerts more powerful effects on long-term exercise adherence than any other single variable except perhaps exercise enjoyment itself — and the two are deeply interrelated, since exercise that occurs in positive social contexts is typically experienced as more enjoyable than equivalent exercise performed in social isolation.

6. Building Your Personal Progress Tracking System

Knowing what to track is only useful if you build a tracking system that you will actually use consistently — one that is simple enough to maintain without significant overhead, comprehensive enough to provide the multi-dimensional progress picture that single-metric tracking cannot, and structured in a way that produces actionable insights rather than just data accumulation.

6-1. The Minimum Viable Tracking System

The minimum viable progress tracking system for a recreational fitness enthusiast who wants meaningful progress data without excessive measurement overhead: weekly morning weigh-in (one reading per week, same conditions), monthly waist circumference measurement, monthly performance benchmark (maximum push-ups and pull-ups, or 5K time, depending on goals), and monthly progress photo (front and side, standardized protocol). This four-component minimum system requires approximately 10 minutes per month of measurement time and 5 minutes per week of data entry, produces meaningful trend data across all major progress dimensions within 6 to 8 weeks, and avoids the data-obsession risk of more intensive tracking approaches. For the majority of recreational exercisers, this minimum system provides more than adequate progress information for motivation maintenance, program adjustment decisions, and goal achievement evaluation.

6-2. The Comprehensive Tracking System for Goal-Focused Trainees

For trainees with specific body composition or performance goals who want more detailed progress data: daily morning weight (for 7-day and 4-week rolling averages), weekly BIA measurement under standardized conditions, weekly waist and hip circumference measurements, session-by-session training log (all exercises, sets, reps, loads), monthly formal strength or performance testing, monthly 4-week photo comparison, and weekly subjective energy, sleep, and mood ratings. This comprehensive system requires 5 to 10 minutes of daily logging (primarily the training log), 10 minutes of weekly measurement, and 20 to 30 minutes of monthly assessment — a total of approximately 2 hours per month of measurement and assessment time that provides the complete, multi-dimensional progress picture needed for precise program management and goal achievement evaluation.

6-3. Digital Tools and Apps for Progress Tracking

Dedicated fitness tracking applications significantly reduce the friction of maintaining comprehensive progress records by automating data visualization, trend calculation, and multi-metric comparison across time. Strong and Hevy (training log apps that automatically calculate volume, track progressive overload, and graph strength trends) eliminate the manual calculation burden of detailed training logs. Happy Scale and Libra (weight trending apps that automatically calculate rolling averages and filter daily fluctuation noise) transform daily weight data into clean trend lines that correctly represent actual body composition changes beneath scale noise. MyFitnessPal and Cronometer (nutrition tracking apps) provide the caloric and macronutrient tracking data that contextualizes body composition change rates. Strava, Garmin Connect, and Apple Health aggregate cardiovascular performance data automatically from GPS and wearable sensors. A combination of 2 to 3 of these apps — selected to cover the progress dimensions most relevant to the individual’s specific goals — creates an integrated digital progress tracking system that requires minimal manual data entry while providing comprehensive, automatically visualized progress data.

6-4. Monthly Progress Reviews

Raw progress data is only valuable if it is reviewed and interpreted in a structured way that connects observations to training and nutrition adjustments. A monthly progress review — spending 20 to 30 minutes comparing current metrics to the previous month’s measurements and the goal trajectory established at the beginning of the training block — provides the regular feedback loop that allows intelligent program management rather than passive data accumulation. The monthly review addresses three questions: Is progress on track toward the current milestone goal? If yes, maintain current approach. If no, is the gap between expected and actual progress driven by insufficient process execution (training consistency, nutritional adherence, sleep quality) or by a genuine program efficacy issue (the program producing less adaptation than the physiology research would predict)? Process gaps require behavioral changes; program efficacy gaps require program modifications. Answering these questions with the multi-metric data that the comprehensive tracking system provides produces far more accurate diagnoses and more effective adjustments than the single-metric scale reading that most people use to evaluate whether their approach is working.

6-5. Avoiding Tracking Obsession and Measurement Anxiety

The comprehensive progress tracking system described in this section is intended to provide better information for better decisions — not to create a new source of anxiety or a new focus for body-related obsession. Signs that the tracking system has crossed from informative to counterproductive: daily measurement results significantly affecting mood regardless of their actual significance; inability to enjoy training on days when recent measurement results have been disappointing; reducing food intake or increasing exercise beyond planned levels based on individual measurement readings rather than multi-week trends; or spending more time analyzing measurement data than training. These signs indicate that the tracking system is being used as a control mechanism rather than an information tool, and that recalibrating the emotional relationship with the data — by increasing measurement intervals, reducing the number of metrics tracked, or temporarily suspending measurement to reconnect with the intrinsic enjoyment of training — is appropriate. The tracking system serves the fitness journey; the fitness journey should never be held hostage to the tracking system.

| Tracking Level | Time per Week | Metrics Covered | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum viable | ~5 minutes | Weight, circumference, performance, photos (monthly) | Habit-building phase; casual fitness |

| Comprehensive | ~20–30 minutes | All above + daily log, BIA, subjective metrics | Active goal pursuit; body composition focus |

| Advanced | ~45–60 minutes | All above + DEXA, detailed performance testing | Competitive preparation; precision recomposition |

6-6. Communicating Progress Data with Healthcare Providers

The comprehensive progress data that a multi-metric fitness tracking system produces has clinical value beyond its utility for individual training management — it provides healthcare providers with objective, longitudinal fitness data that most patients do not bring to clinical appointments and that most clinicians do not systematically collect. Blood pressure trends, resting heart rate changes, waist circumference measurements, body composition data, and functional fitness assessments are all clinically relevant metrics that directly inform the management of common chronic conditions including hypertension, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease risk, and musculoskeletal conditions — yet this data is rarely available at clinical appointments because few patients collect it systematically between visits. Bringing a concise summary of key fitness metrics to annual physical examinations or chronic disease management appointments provides clinicians with objective functional health data that laboratory tests and office-based measurements cannot fully capture, enabling more precise and more personalized health management than the episodic clinical measurement alone supports.

The specific fitness metrics with the most clinical relevance to share with healthcare providers: resting heart rate trend (a declining trend indicates improving cardiovascular fitness; an unexpected increase may signal overtraining, illness, or other health issues); waist circumference trend (directly relevant to cardiometabolic risk assessment); blood pressure (if self-monitored at home — tracking trends between clinical visits provides more representative data than single-point-in-time clinical measurements affected by white coat hypertension); and exercise capacity (distance covered in a fixed time, or time required to complete a fixed distance — a practical proxy for cardiorespiratory fitness that correlates strongly with all-cause mortality in epidemiological research). Healthcare providers who receive this longitudinal fitness data from engaged, self-monitoring patients can provide more specific lifestyle modification guidance based on actual physiological responses rather than generic population-average recommendations, more accurate and individually calibrated health risk assessment that accounts for the patient’s specific fitness trajectory, and more appropriate and precisely timed adjustment of any pharmacological management that intersects with the physiological changes that fitness development produces — making the comprehensive tracking system genuinely valuable for clinical partnership and health management in addition to its primary fitness progress monitoring and training optimization utility.

The electronic health record integration that some fitness tracking platforms and wearable manufacturers now offer — automatically syncing continuous health monitoring data including resting heart rate trends, activity levels, sleep architecture data, and blood oxygen saturation directly with patient health records accessible to clinical providers — represents the emerging frontier of this clinical-fitness data integration. This automated integration is currently available only in some healthcare systems, requires explicit patient consent, compatible technological infrastructure between the tracking platform and the clinical record system, and clinical provider willingness to incorporate consumer-grade wearable data into clinical decision-making — prerequisites that are not universally met but that are becoming progressively more common as healthcare systems recognize the clinical value of continuous real-world health monitoring that wearable technology enables. Where this integration is available, it eliminates the manual data presentation burden from the patient and makes fitness tracking data automatically available to the clinical team in the context where clinical decisions are made — potentially enabling more responsive clinical management of conditions where fitness-related physiological changes drive ongoing treatment adjustments. For individuals managing specific health conditions — hypertension, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, metabolic syndrome — coordination between the fitness tracking system and clinical monitoring is particularly important. The blood pressure reductions, blood glucose improvements, lipid profile changes, and bone density maintenance that resistance training and cardiovascular exercise produce in these populations are documented, significant, and clinically actionable — but only if they are being measured and communicated to the clinicians managing the condition. A person with type 2 diabetes who implements a consistent resistance training program may experience blood glucose improvements that warrant medication adjustment — an adjustment that can only be made appropriately if both the patient and the clinician are aware of the training-induced metabolic changes that are driving the improvement. The fitness tracking system that captures these health metrics creates the communication bridge between the patient’s lifestyle changes and the clinician’s management decisions that produces the best health outcomes from the combination of medical and lifestyle intervention.

7. Interpreting Your Progress Data: What Different Patterns Mean

Collecting progress data is the first step; interpreting it accurately to distinguish genuine progress from noise and genuine plateaus from normal variation is the skill that makes the data actionable.

7-1. The Successful Recomposition Pattern

A successful body recomposition pattern — simultaneous fat loss and muscle gain — produces a characteristic multi-metric signature that looks like failure on the scale but success on every other metric. Scale weight: unchanged or slightly increased. Body fat percentage: decreasing. Lean mass: increasing. Waist circumference: decreasing. Strength performance: improving. Progress photos: showing a leaner, more muscular physique despite unchanged scale weight. Subjective energy and mood: improving. This pattern is frequently misinterpreted as program failure when the scale is the only metric tracked, and correctly interpreted as excellent progress when the full metric portfolio is evaluated. The ability to recognize the recomposition signature in the data is one of the most important analytical skills in fitness progress interpretation — and one that is impossible without the multi-metric tracking that this guide advocates and impossible to make with scale-only data that provides no lean mass, body fat, or circumference information.

7-2. The Fat Loss Progress Pattern

Successful fat loss produces a multi-metric pattern that includes: scale weight trending downward at 0.25 to 1.0 kilograms per week (after filtering daily fluctuation through rolling average); body fat percentage decreasing; waist and hip circumference decreasing; progress photos showing less body fat with maintained or improved muscle definition; strength performance maintained or slightly reduced (some strength loss is normal and acceptable in a significant caloric deficit); and subjective energy potentially slightly reduced (caloric restriction reduces available energy) but mood often improved by the physical progress visibility. The critical diagnostic for distinguishing successful fat loss from insufficient progress: if process goals (caloric deficit, training consistency) are being executed at the planned rate, the expected fat loss should emerge in the scale trend data within 3 to 4 weeks. If process goals are being executed but scale trend is flat over 4 weeks, the actual caloric deficit may be smaller than calculated — often due to metabolic adaptation, calorie-tracking errors, or untracked caloric intake. If process goals are not being executed consistently, the fat loss shortfall is behavioral rather than physiological and requires process rather than program changes.

7-3. The Muscle Building Progress Pattern

Successful muscle building during a caloric surplus phase produces: scale weight trending upward at 0.25 to 0.5 kilograms per week (a higher rate suggests excessive fat gain); lean mass increasing on body composition measurements; strength performance consistently improving across the training program; progress photos showing increased muscle size and improved body shape despite some fat accumulation; waist circumference stable or slightly increasing (some fat gain accompanies muscle gain in a true surplus); and subjective energy high from adequate caloric intake. The critical diagnostic: strength improvement is the most reliable real-time signal of muscle development in a surplus phase. If strength is consistently progressing across the major lifts, muscle development is almost certainly occurring regardless of what the scale or the mirror shows in any given week. If strength is stagnant despite consistent training and adequate nutrition, the training program, recovery quality, or caloric surplus magnitude may require adjustment to stimulate continued muscle development.

7-4. Plateau Patterns: When to Adjust and When to Wait

Distinguishing a genuine training plateau from a temporary progress stall that requires patience rather than program change is one of the most practically important and most commonly miscalibrated skills in fitness progress management. The general rule: 2 to 3 weeks of stagnant progress metrics despite consistent process-goal execution is insufficient data to conclude a plateau — this duration is within the normal variability of physiological adaptation timelines. Four to six weeks of stagnant progress metrics across multiple measurement dimensions despite consistent, verified process-goal execution is a genuine plateau signal that warrants systematic program evaluation. The evaluation should address, in order: caloric intake and expenditure (is the energy environment appropriate for the stated goal?), protein intake (is protein consumption adequate to support the muscle-related goal?), training volume and progressive overload (is the training providing sufficient stimulus, and is overload being systematically applied?), recovery quality (is sleep duration and quality adequate for adaptation?), and training program design (are the exercise selections, frequency, and intensity appropriate for the goal?). Identifying the specific variable most likely to be limiting progress — rather than making wholesale program changes based on the vague sense that “something isn’t working” — produces more effective adjustments and less unnecessary disruption to the program consistency that long-term results require.

7-5. The Long-Term Progress Perspective

Monthly progress comparisons are motivating and informative, but the most accurate and most inspiring perspective on fitness progress requires the longer time horizons that reveal the cumulative transformation that months of consistent monthly progress produce. Comparing current metrics to metrics from 6 months ago, 1 year ago, and 2 years ago provides perspective on the magnitude of long-term fitness development that monthly comparisons cannot capture — because the changes that seem modest month-to-month compound into transformations that are genuinely dramatic at the 12 to 24-month scale. The person who loses 1 kilogram of fat and gains 0.5 kilograms of muscle per month — progress that looks unremarkable in any single month — has lost 12 kilograms of fat and gained 6 kilograms of muscle in a year, a transformation that represents a genuinely significant change in health, appearance, and physical capability. Maintaining the long-term progress perspective — regularly comparing current state to 12 and 24-month-ago baselines in addition to the more frequent short-term comparisons — sustains the motivational context for continued training that short-term-only evaluation cannot provide when individual months are disappointing.

| Progress Pattern | Scale | Body Fat % | Strength | Photos |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recomposition ✅ | Stable | ↓ Decreasing | ↑ Improving | Leaner + more muscular |

| Fat loss ✅ | ↓ Trending down | ↓ Decreasing | Stable/slight drop | Less fat, maintained muscle |

| Muscle building ✅ | ↑ Trending up slowly | Stable/slight rise | ↑ Consistently improving | More muscular |

| Plateau ❌ | Stable 4–6 weeks | Stable 4–6 weeks | Stagnant 4–6 weeks | No change 4–6 weeks |

7-6. The Long-Term Progress Mindset

The ultimate goal of the comprehensive progress tracking system described in this guide is not to create a permanent, elaborate measurement infrastructure that runs alongside fitness training indefinitely — it is to provide the objective feedback needed during the active goal-pursuit phases of the fitness journey while building the self-awareness and experiential knowledge that eventually make extensive external measurement less necessary. The experienced exerciser who has trained consistently for 3 to 5 years develops an increasingly accurate intuitive sense of their body’s response to training and nutrition — they can feel the difference between effective training and ineffective training, recognize the signs of overtraining before formal metrics confirm it, and accurately estimate their energy balance without daily food tracking. This experiential self-knowledge develops through the consistent practice and systematic self-observation that the tracking system enables during the development phase — making the tracking system a genuine, time-limited developmental tool that progressively and irreversibly builds practical measurement capability, deep physiological self-knowledge, and authentic long-term body literacy rather than a permanent dependency that indefinitely replaces the internalized self-monitoring competence that only years of consistent, attentive, and genuinely curious practice can develop.